Academic or scientific conferences tend to be a bit more formal than most presentations. It’s not so much about entertaining as getting the information across – but that doesn’t mean you have to be boring. Remember you are there to GIVE a paper not READ a paper. The audience may already have your paper and they can read it themselves. Your job is to present the highlights, draw attention to key points, possibly provide some additional background. And ultimately encourage them to read your paper and perhaps follow up with you.

Most academic conferences have a clear structure. There will be keynote or plenary sessions where the whole audience attends. Then there are likely to be a series of parallel sessions/workshops and probably a poster session.

Keynotes and plenary sessions

If you are lucky enough to be invited to give a keynote address then you need to take it seriously and prepare very well. The audience is likely to be large and you will want to impress.

If you are lucky enough to be invited to give a keynote address then you need to take it seriously and prepare very well. The audience is likely to be large and you will want to impress.

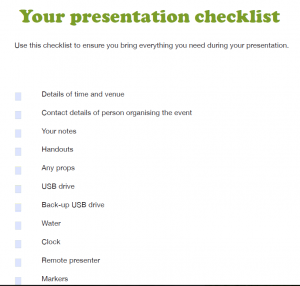

Things to do are:

- read the instructions – find out what the usual format is and stick to it

- find the convenor and introduce yourself

- make sure you give good biographical details to the person who will introduce you

- ask the convenor to give you a sign as you get close to the end time, for example, a five minute warning

- agree with the convenor on how you are going to handle questions

- find out about some of the other talks at the conference – you may want to refer to them in your talk

- get the technical staff to check and double check all of the equipment

Parallel sessions

Parallel sessions are usually run in a block, for example, three or four presentations of about 15–20 minutes each. Obviously less people will attend each of these as the audience is spread over several sessions.

If you are giving one of these sessions there are a few things to remember:

- make sure you have your PowerPoint loaded before the series or block begins, there won’t be time for a handover in the middle

- normally there will be a moderator or convenor. Make a point of meeting them beforehand. If you want to be introduced in a particular way you can let them know. Check with them how questions are going to be handled. Will it be after each session or at the end of the block?

- get a clock or watch so that you can keep a track of when you are on and where you are up to

- get there early to check out the lectern and controls. You may not have time immediately before your talk

Have a look at the abstracts for the other speakers in your block. Will they be saying similar things to you or contradicting you? Do you need to modify your content based on what they will say? For example, if one of them steals your best line or joke do you need to have a back-up?

A problem with parallel sessions is that the previous speaker may run over time. This could cut down your time. You then have to think about which parts of your talk you could speed up or drop out. Perhaps you might allow less time for questions (yippee!)

Adapted from Presenting your Research with Confidence, Hugh Kearns.